Webinar: Let's make a programming language. Part 1. Intro - 20.02

Devs often use "magic code" to solve tree problems on LeetCode. However, enterprise code requires readability and maintainability for years. What shall we do when a task is so large that completing it manually would take weeks? Let's take a look at how code generation can help.

In the previous article, we examined a problem of tree translation. There, we scrutinized how it could be decomposed and proposed a solution. If you want to start with the basics, I suggest taking a peek there.

However, I briefly rewind to what we'll discuss.

What shall we do? We need an AST translator from the TypeScript compiler representation to our own.

For what? To develop a static analyzer for JavaScript/TypeScript.

An abstract syntax tree (or AST) surprisingly has not so many differences from any other tree. I'd like to highlight two important characteristics: it has many different types of nodes (for each syntactic structure in the language), and the trees can grow quite large, even though operations on the nodes remain standard. In the last article, we defined three types of operations:

() => true to () => { return true }.In the previous article, we concluded that we needed to translate a tree consisting of 263 nodes into our tree of ~100 nodes. This means that one of the operations would have to be implemented at least a hundred times manually. These are thousands of identical code lines that must be carefully written and then meticulously maintained. Of course, we could do it by hand, but there's a better option, and it is code generation.

So, we want to generate code. The Java build system allows us to add additional files during the build; we're not limited here.

The task seems simple: take a StringBuilder and do append as many times as we can—and for trivial cases, this may work, but even a slight complexity, like indents, causes problems.

To simplify our lives and avoid reinventing the wheel, it's better to use an existing tool. There are several options:

With the right tool in hand, we can start exploring how to use it.

Great things have small beginnings, so I'll demonstrate JavaPoet functionality with the well-known "Hello World" example:

public static JavaFile createMain() {

var main = MethodSpec.methodBuilder("main")

.addModifiers(Modifier.PUBLIC, Modifier.STATIC)

.returns(void.class)

.addParameter(String[].class, "args")

.addStatement("$T.out.println($S)",

System.class,

"Hello world!")

.build();

var hello = TypeSpec.classBuilder("Main")

.addModifiers(Modifier.PUBLIC, Modifier.FINAL)

.addMethod(main)

.build();

return JavaFile.builder("com.example.generated", hello)

.indent(" ")

.build();

}After saving to a file, we got:

package com.example.generated;

import java.lang.String;

import java.lang.System;

public final class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

System.out.println("Hello world!");

}

}To understand what JavaPoet offers, we'll examine the API on the example above, and it'd be enough for our purposes. At the same time, I'll try to briefly overview the framework.

JavaFile is used for determining where we write our code to, including methods for writing to files. We can add a package and comments here.TypeSpec provides builders for creating types. They have everything: modifiers, fields, methods, and so on. FieldSpec defines class fields.MethodSpec is similar to the previous ones; it allows us to define a method. To avoid writing the entire method body in one place, we can immediately pass CodeBlock to addStatement. Defining the method body in a separate location isn't the only thing that CodeBlock offers. Do you remember when I mentioned indents? This task is being solved here. We don't need to worry about where to add braces and indents: with block.beginControlFlow("if ($L > 0)", "x") and block.endControlFlow(), we automatically open and close the code block:

if (x > 0) {

}Examples of usage will appear later in the text.

In the examples above, we may notice that the written code lines contain patterns such as $L and $T. The first is literal substitution, the second is type substitution, which helps with imports.

Literal substitution is a simple thing because it inserts whatever we pass to it. Handling types, however, is a bit trickier. In the "Hello World" example, the class is passed directly. We can use primitive types via TypeName, but the module where we're writing the code generator may have no access to the type we need. The next section explains how to handle it.

If we need to refer to an arbitrary class, we need ClassName. It's defined as simply as possible: ClassName.get("com.example.package", "ClassName"). They can be used in the previously mentioned $T pattern.

ClassName will be needed frequently, so it's better to cache it.

Finally, we can move on to the promised tree translation. Last time, I showed how to perform the three transformations mentioned earlier using a visitor. I'll repeat the code:

interface Visitor<R, P> {

R visitBinary(Binary n, P parent);

R visitLiteral(Literal n, P parent);

}

class Builder extends Scanner<JsNode, JsNode> {

@Override

public JsNode visitBinary(Binary n, JsNode parent) {

var translated = new JsBinary(n.getKind());

translated.setLeft((JsExpression) scan(n.getLeft()));

translated.setRight((JsExpression) scan(n.getRight()));

return translated;

}

@Override

public JsNode visitLiteral(Literal n, JsNode parent) {

var literal = new JsLiteral(n.getValue());

literal.setParent(parent);

return literal;

}

}Here we can see an isomorphism of a binary operation using the visit-type method:

By recursively traversing the source tree this way, we obtain the target tree root.

As outlined earlier, we have a plethora of node types that need to be handled manually. Obviously, we can't get away from writing the logic of the translation—collecting and linking nodes—but there are many code repeats: method declarations, annotations, similar calls, and type conversions. In short, it's boilerplate, which we can avoid using code generation.

How can we eliminate boilerplate in the Java code while preserving the logic? Just don't use Java! Instead, any other format that our self-written generator can read will be a good option. Personally, I chose YAML because its nested structure fits our needs well.

First, we need to define an isomorphic transformation, i.e., simply specifying which node in the target tree each source node maps into:

CallExpression:

target: JsInvocation

args:

- getQuestionDotToken()Here, we translate the CallExpression node into JsInvocation, additionally specifying that the result of the getQuestionDotToken() call on the source node should be passed to the constructor.

We simply moved some Java code into a separate file, which the generator then uses to create Java code from the template. As a result, we got a simple and punchy pseudo-DSL. The main advantage lies in preserving a consistent generation pattern: we set the mapping between nodes and their bindings, ensuring its correctness via Java typing and build- and test-level checks.

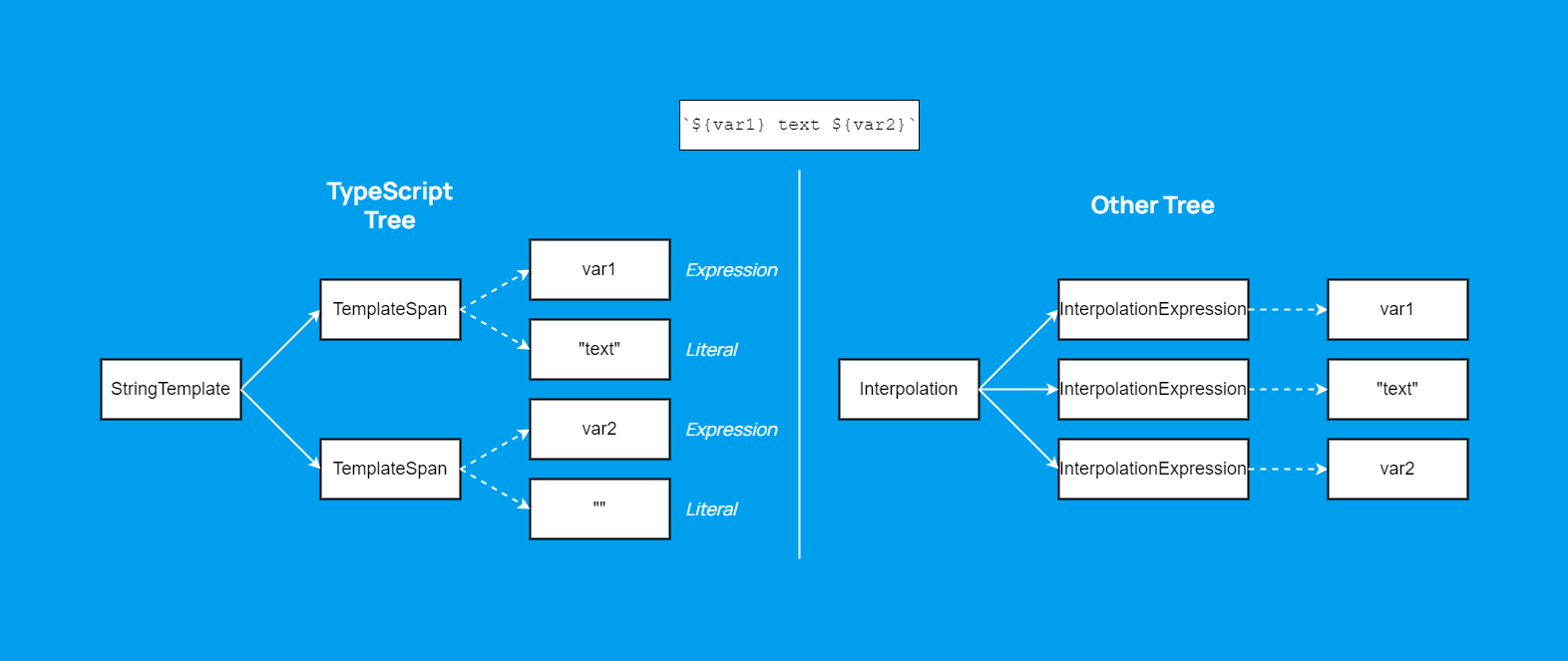

Secondly, we should not forget about decomposition. Here's an example with string interpolation from the previous article, where we split TemplateSpan into InterpolationExpression:

We can describe it like this:

TemplateSpan:

- member: Expression

target: JsInterpolationExpression

- member: TemplateTail

target: JsInterpolationTextA JsInterpolationExpression should be created from the Expression property of the TemplateSpan node, and JsInterpolationText from the TemplateTail.

Thirdly, we need to connect parent and child nodes somehow. Binding children to parents is straightforward: we create a stack of elements and use the top of the stack as the parent node. But what about binding parents to children? How do we know whether an Expression is the right or left operand of a binary expression? Or is it an argument for a function call?

To do this, we define roles:

BINARY_LEFT:

parentAs: JsBinaryExpression

nodeAs: Expression

invoke: setLeft

BINARY_RIGHT:

parentAs: JsBinaryExpression

nodeAs: Expression

invoke: setRightThey define how child nodes are attached to a parent and how nodes are cast based on their role. In code, the role will be set when scanning a node property.

The remaining step is to specify roles for the tree node properties:

BinaryExpression:

- member: Left

role: BINARY_LEFT

- member: Right

role: BINARY_RIGHTWe assign the corresponding roles to the left and right operands of the binary expression.

This way, we reduce the number of handwritten lines from thousands to hundreds, leaving only those that contain actual logic. The next step is to understand how to generate code based on the configuration.

We've decided how we'll generate the code, but we haven't yet figured out what exactly will be generated. Although I've given some hints: we need a context (state) of the translation based on a stack.

Let me remind you that we already have a generated visitor and walker for the source tree, as described in the previous article. So, the base for mounting the translator is ready.

First, I'll reproduce under the spoiler what a functional visitor looks like.

class Builder extends Scanner<JsNode, JsNode> {

@Override

public JsNode visitBinary(Binary n, JsNode parent) {

var translated = new JsBinary(n.getKind());

translated.setLeft((JsExpression) scan(n.getLeft()));

translated.setRight((JsExpression) scan(n.getRight()));

return translated;

}

@Override

public JsNode visitLiteral(Literal n, JsNode parent) {

var literal = new JsLiteral(n.getValue());

literal.setParent(parent);

return literal;

}

}I called it "functional" because it's always busy returning something. We can rewrite it to stack-based, where stacks are used for parent nodes and roles instead of call results, like this:

class Builder extends Scanner {

private final Deque<JsNode> elements = new ArrayDeque<>();

private final Deque<Role> roles = new ArrayDeque<>();

@Override

public void visitBinary(Binary n) {

var translated = new JsBinary(n.getKind());

elements.push(translated);

roles.push(Role.BINARY_LEFT);

scan(n.getLeft());

roles.pop();

roles.push(Role.BINARY_RIGHT);

scan(n.getRight());

roles.pop();

elements.pop();

if (!elements.isEmpty()) {

var parent = elements.peek();

var role = roles.peek();

translated.setParent(parent);

if (role == Role.BINARY_LEFT) {

((JsBinaryExpression) parent).setLeft((Expression) translated);

} else if (role == Role.BINARY_RIGHT) {

((JsBinaryExpression) parent).setRight((Expression) translated);

}

}

}

@Override

public void visitLiteral(Literal n) {

var literal = new JsLiteral(n.getValue());

var parent = elements.peek();

var role = roles.peek();

literal.setParent(parent);

if (role == Role.BINARY_LEFT) {

((JsBinaryExpression) parent).setLeft((Expression) literal);

} else if (role == Role.BINARY_RIGHT) {

((JsBinaryExpression) parent).setRight((Expression) literal);

}

}

}Here, the roles stack appears, where we set which role to use when scanning a child node. Depending on it, the child node determines how exactly to connect itself to the parent. The parent, in turn, is taken from the elements stack. Roles are duplicated for both literals and binary expressions because binary expressions can be subexpressions.

Thanks to stacks, the code becomes more uniform and consists of discrete operations, which is good for us because we need to generate code. In addition, there's no need to support several different visitors for cases when the project requires ones that neither accept parents and nor return anything.

On the other hand, the example looks clumsy, but I deliberately simplified it for clarity. The code can definitely be improved:

Builder into separate parts—creating nodes, scanning, and processing their finalization here—because it's the only one here and does everything at once. try-with-resources syntax to reduce visual noise.switch statement, rather than clutter nodes with duplicate if statements.Actually, that's exactly what I did in the project. The steps roughly follow this order:

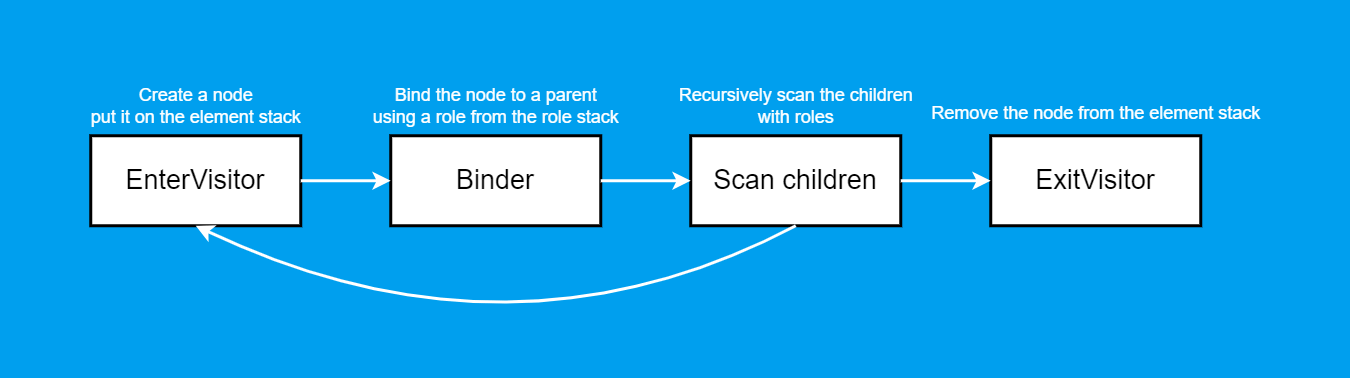

EnterVisitor creates a node and places it on the stack;Binder contains a giant switch with all roles and binds parents with children in both directions;Walker (Scan children) places roles on the stack and scans child nodes with those roles. During decomposition, it also places elements created from node properties onto the stack. The scan is recursive, so for each child element we'll again enter EnterVisitor;ExitVisitor removes the element from the stack.We sought to achieve consistent code, but we need to factor in normalization, which by definition is a certain arbitrary action. How can this be addressed?

As shown in the diagram above, I have replaceable EnterVisitor and ExitVisitor, and for Walker, we can define any code after traversal but before extracting the current element from the stack.

Let's look at this through the example of entry and exit visitors. EnterVisitor and ExitVisitor are created through factories, where the default factory performs a direct conversion from YAML. To completely replace this logic, we just need to register a factory that will generate what we need instead of standardized code. For example:

public class VisitFile implements VisitGenerator {

@Override

public CodeBlock generateEnter() {

return CodeBlock.builder()

.addStatement("var file = new $T()",

ClassName.get(filePkg, "JsCodeFile"))

.addStatement("ctx.getElements().push(file)")

.addStatement(

"file.setPosition($T.startPosition($T.of(src.getPath())))",

ClassName.get(posPkg, "SourcePosition"),

ClassName.get(Path.class))

.build();

}

@Override

public CodeBlock generateExit() {

return CodeBlock.builder()

.addStatement("file = (JsCodeFile) ctx.getElements().pop()")

.build();

}

}The generated entry visitor method will look like this:

public void visitFileNode(FileNode src) {

var file = new JsCodeFile();

ctx.getElements().push(file);

file.setPosition(SourcePosition.startPosition(Path.of(src.getPath())));

}And the exit visitor method will look like this:

public void visitFileNode(FileNode src) {

file = (JsCodeFile) ctx.getElements().pop();

}This factory helps us add special processing to the input position and assignment to the output field.

However, directly modifying Walker methods or replacing visitor methods can lead to issues:

Let's sum up. Although the decision is not optimal, we've reached the desired compromise:

It's now 2026, and I'm completely ignoring current trends. Writing a large amount of boilerplate code? That's literally a case for AI agents. The idea did cross my mind, but let me explain why I didn't go that route:

This is the end of the dilogy about the tree translation. It turned out to be quite an unusual problem, which resulted in a series of two developer's notes. I hope that these articles helped you learn more about trees and code generation. Please share in the comments if you've ever run into similar problems.

While this series ends here, we'll continue publishing articles about the new analyzer. To keep up with us, subscribe to PVS-Studio on X and our monthly article digest. You're welcome to try the tool for free.

If you'd like to follow my posts, subscribe to my personal blog.

0