Analyzing source code is a challenging task, especially when it comes to identifying potential vulnerabilities. In this article, we'll share how we traced data flow passing through object fields.

For taint analysis, we need to trace the data flow that passes through object fields. This technology is important for deep code analysis in any language, but in this article, we'll discuss its implementation specifically for our Java analyzer.

In short, taint analysis is an essential component of static code analysis. It detects potential vulnerabilities that involve unverified external data in specific parts of code. One of the most well-known and easy-to-understand examples of such a vulnerability is SQL injection.

If you'd like to learn more about taint analysis, we recommend reading the following articles:

Before we go into why we need to trace data passing through fields, let me just remind you of the taint analysis basics.

The main goal of the taint component of the analyzer is to determine where data used in a sensitive point—the so-called sink—originally came from. A sink can be anything from an executable SQL expression to a command passed to the operating system or a file path. When the analyzer detects that data comes from an external source and never gets sanitized or checked along the way, it issues a warning.

Let's look at an example of a Path Traversal vulnerability to see how it works:

@RestController

public class FileController {

@GetMapping("/read")

public List<String> read(@RequestParam String relativePath) {

Path requestedPath = Path.of("D:/someFolder/content/" + relativePath);

return Files.readAllLines(requestedPath);

}

}Here, the relativePath string comes from a web parameter to the read method. We treat it as tainted data. The code then builds an absolute file path by concatenating it with the someFolder/content root path. The resulting path goes straight to the sink, Files.readAllLines.

The analyzer detects that tainted data gets into the sink and issues the following warning for this code:

V5332 Possible path traversal vulnerability. Potentially tainted data in the 'requestedPath' variable might be used to access files or folders outside a target directory.

However, if tainted data is checked or sanitized before entering the sink, the analyzer won't issue any warnings.

In order to detect critical errors and potential vulnerabilities, the analyzer needs to understand how data flows through the program. As part of the taint analysis process, we use DU chains to check the definitions and uses of a particular variable within a method. In short, it's a graph that goes from obtaining a variable value to all of its uses.

When another variable is used to determine a variable, we connect the chains for them. These connections result in a unique data-flow graph, which we use to see how data flows between variables in the method.

My colleague described this in more detail in his article. I highly recommend reading it. And this is what our unique data-flow graph for the code above looks like.

The code:

@RestController

public class FileController {

@GetMapping("/read")

public List<String> read(@RequestParam String relativePath) {

Path requestedPath = Path.of("D:/someFolder/content/" + relativePath);

return Files.readAllLines(requestedPath);

}

}DU chains:

This image shows the DU chains: one for the requestedPath variable and the other for relativePath. The arrow on the graph leads from the variable definition to its use.

The traversal starts with the requestedPath variable, which is used in the sink. Having reached its definition, we see that it's based on relativePath. Using a simple API, we move on to the chain for relativePath. The dotted line on the diagram shows this transition. We move to its definition and see that it came from an external source.

This is how we learned that the path is formed based on external data. As a result, the analyzer issues a warning.

In the example above, external data flows through local variables. Until recently, that was the only kind of data flow we could track. What happens, though, when data moves through object fields? DU chains cover only the variables, not the fields they contain.

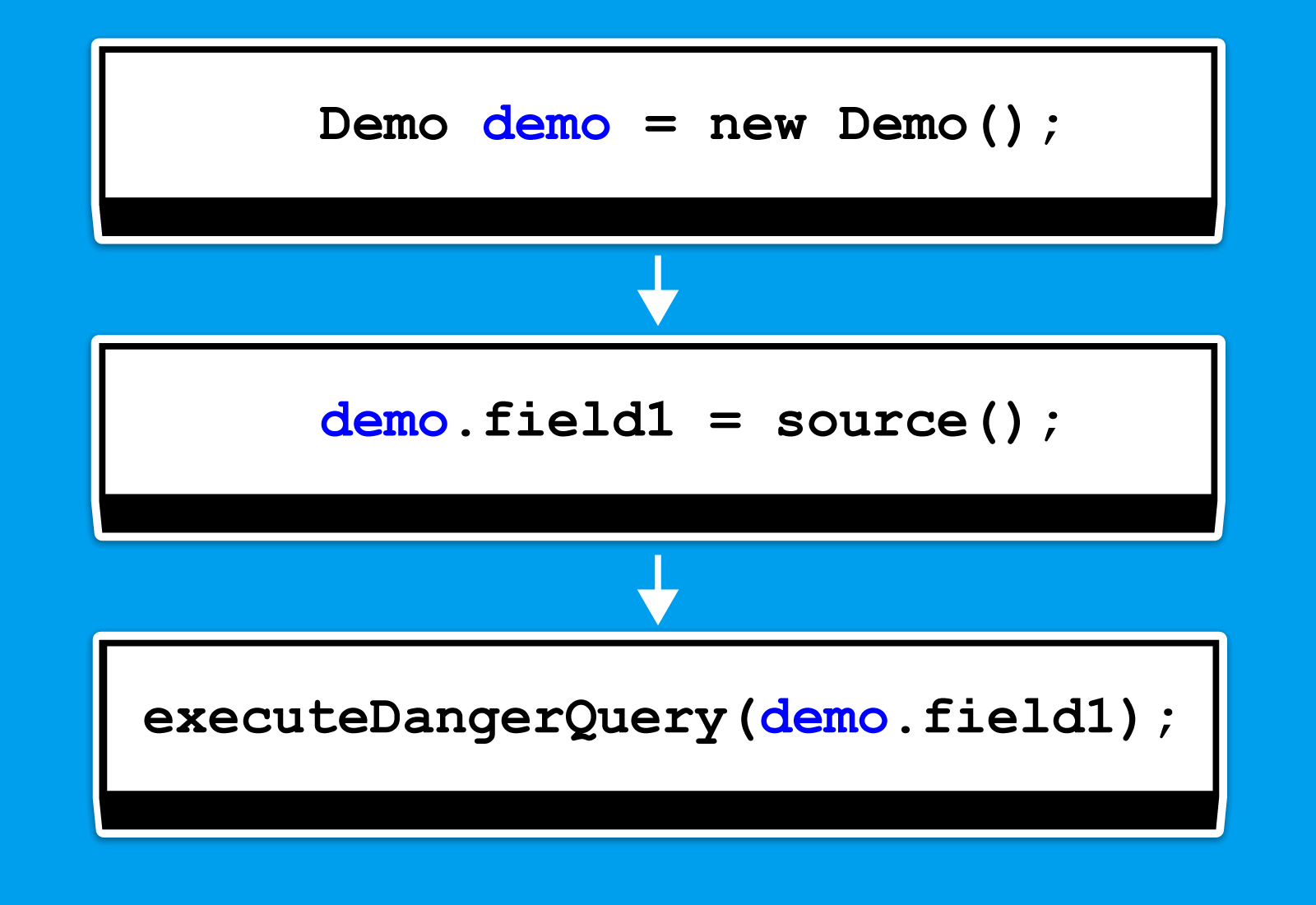

Judging by the title of this section, it's clear that we didn't know how to work with this type of data at first. For example, we were powerless in the following cases:

void test() {

Demo demo = new Demo();

demo.field1 = source();

executeDangerQuery(demo.field1)

}So, if the data we're checking somehow passes through the fields of a certain object, we lose track of it during the traversal. We initially avoided this because the task was challenging and required more than just creating and traversing DU chains for fields. However, it's time to return to it.

Here comes the question, "What exactly is the issue? This doesn't look like a complicated thing." Firstly, we need to choose an approach that naturally fits into the traversal algorithm described above. Secondly, field handling involves more complex cases.

Here's the simple example:

void test() {

Demo demo = new Demo();

demo.field1 = source();

executeDangerQuery(demo.field1)

}We have the following chain for the demo variable:

We just need to properly traverse the chain for this object to understand whether its field1 field, which is used in the stack, is tainted. What did we add to our traversal?

When we see a sink use a field of some object, we create a special container. It stores a reference to the object and tracks the specific fields that appear in the sink. We mark those fields as relevant. In the example above, the object would be demo, and the field would be field1.

As we move up the chains for demo, we look at what happens to the object and its fields. If we see the field get sanitized, we remove it from the container. If the container ends up empty, we stop the traversal.

Extending the algorithm to cover this simple case was unnecessary, but a slightly more complex case would look like this:

class Demo {

void test(Demo other) {

other.str = source();

Demo newObject = other;

executeDangerStatement(newObject.str);

}

}We also use the str field here, but its value changes depending on the object to which it belongs when we assign the newObject variable to other. If we built DU chains for the str field and tried to follow them, we'd reach the end of the traversal there.

Containers streamline this process. While traversing the chain for newObject, we encounter the Demo newObject = other assignment. Then, we copy the container to other and continue the traversal along the variable. When we reach other.str = source(), we see that the str field appears in the container, and the analyzer issues a warning.

The same system can handle the complex cases mentioned earlier in the article.

var a = new A();

a.field = "value";

a = null;

var b = a.field;Since we're still traversing variable chains rather than their fields, we see the variable reset to zero and stop the traversal. However, we should still build chains for the fields. This is necessary for more precise branching, though it doesn't change things overall.

To verify whether a given fix works as intended, we create test artifacts—code snippets for which the analyzer should issue warnings or ignore when no error exists. One such example looks like this:

public class SpecialConnection {

private String entityName = null;

private Connection connection;

....

public ResultSet executeQuery(HttpServletRequest externalRequest) {

ResultSet result = null;

try (Statement stmt = connection.createStatement()) {

if (entityName == null) {

entityName = externalRequest.getParameter("entity");

}

String query = String.format(

"SELECT * FROM %s WHERE active = 1",

entityName

);

result = stmt.executeQuery(query);

}

catch (SQLException e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

return result;

}

}PVS-Studio warning: V5309 Possible SQL injection. Potentially tainted data in the 'query' variable is used to create SQL command.

In this case, if the entityName field of the this object is null, the code initializes it with a value taken from a query. The code then uses this entityName value in a database query. Here, the analyzer highlighted the use of external data in the SQL query.

The analysis also handles cases with branching:

class Demo {

DocumentBuilderFactory factory;

private static DocumentBuilderFactory getSafeFactory() {

DocumentBuilderFactory newFactory = DocumentBuilderFactory.newInstance();

newFactory.setFeature(

"http://apache.org/xml/features/disallow-doctype-decl",

True

);

return newFactory;

}

public void example(Demo demo, boolean flag, String textFile)

throws ParserConfigurationException, IOException, SAXException {

factory = getSafeFactory(); // safe

demo.factory = DocumentBuilderFactory.newInstance(); // unsafe

if (flag) {

demo.factory = factory;

}

DocumentBuilder builder = demo.factory.newDocumentBuilder();

builder.parse(textFile); // <=

}

}PVS-Studio warning: V5335. Potential XXE vulnerability. Insecure XML parser in the 'builder' variable is used to process potentially tainted data in the 'textFile' variable.

The previous example is simpler because entityName always comes from an external source. Here, however, the code branches: depending on the incoming flag parameter, the XML parser gets configured either securely or insecurely. We then pass the textFile string, obtained from a public method, to that parser.

The analyzer detected an execution path where an insecurely configured parser processes the string and issued a warning.

The current approach works well when all the relevant context stays within a single method. The limitations of this field-based approach become apparent once data starts flowing from one method to another. Fully passing containers along with their matchings during interprocedural analysis is a costly operation, so we couldn't use the same approach. Instead, we resolved the issue a little differently.

We always annotate the code before taint analysis starts. This way, we identify methods in the standard library and other libraries that could lead to NPEs, division by zero, and other issues. We added one more step to this process before taint analysis: creating a method summary based on field sanitization. If a method sanitizes a field, we add an annotation that marks which field gets sanitized.

For example, when an object sanitizes its own data in another method, we can detect that and avoid issuing a warning:

class Demo {

....

void test(Demo other) {

other.field = source();

other.sanitize();

executeDangerQuery(other.field);

}

void sanitize () {

field = field.removeBadCharacters();

}

}Look at the example: During taint analysis, when we encounter a call to the sanitize method, we check whether it carries the annotation we need. In the above example, it does, and the annotation indicates that the field is sanitized. As a result, we no longer treat the data as tainted.

Although this approach allows us to consider simple interprocedural sanitization, we still can't fully model all possible object states. This is a problem we plan to address next.

We keep improving our Java analyzer, with a particular focus on the taint mechanism. These enhancements make the tool more robust, enabling it to detect subtle bugs and potential vulnerabilities.

Our work on taint analysis doesn't end here. As we implement further improvements, we'll release articles to keep you updated on the latest developments in the analyzer and share some behind-the-scenes stories from its development.

That's all we have for now. If you want to share your thoughts, welcome to the comments.

If you'd like to try our analyzer on your Java, C#, or C/C++ project, just click the link. And if you're developing your own open-source project, you can use PVS-Studio for free to check it. For more information, follow the link.

Best wishes, and see you soon!

0