Webinar: Let's make a programming language. Part 1. Intro - 20.02

Java is expanding with new trendy mechanisms, and along with it, its tomb is growing with outdated features like Vector, Finalization, NashornScriptEngine, SecurityManager, and Unsafe. Let's take a look at these antiquities and see what has replaced them.

Java prospers and grows, accumulating new features, APIs, and modules, but at the same time, it sheds its old skin from time to time. Some parts prove redundant, others no longer fit modern tasks, and some are always intended as kludges. All these outdated or removed mechanisms quietly and steadily fill up Java's tomb.

Let's take a look at some of them.

Back in the days before Java had List, Deque, or Map, savage Vector, Stack, and Dictionary frolicked in the code. Unlike all subsequent antiquities, this outdated API isn't marked as Deprecated, but at the same time, the documentation for each class screams "DON'T USE ME!" On the vastness of the internet, these outdated classes are usually called legacy collection classes.

But why are they outdated?

Legacy collections have two main disadvantages:

Let's go in order.

The first disadvantage is that all interaction points with these classes are synchronized.

However, it feels more like an advantage than the opposite. After all, secure multithreading is always a good thing. But what if these collections are used in a single-threaded context? Synchronizations simply cut performance without providing any real security benefits. This is clearly reflected in modern Java practices, where developers prefer to copy collections rather than modify them.

The second disadvantage is that classes don't have common interfaces and require an individual approach.

This leads to a problem as old as programming itself: non-universal code. Just imagine that we're a developer working on an old Java version, and we have code tied to Stack. For instance, here's one:

Stack<Integer> stack = new Stack<>();

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++) {

stack.add(i);

}

System.out.println(stack.pop());Right now, the code is without any hitch, but imagine that it has ballooned to 1,000 lines with 150 references to the stack variable.

Then one day, customers sent a fax to us, saying they worked very slowly (the code blocks, not the customers). We realize that Stack contains an array for storing elements, and this very array is recreated too often.

We ponder and put forward a theory: the linked list can help boost the app performance by 100 times! Eager to test it, we find some LinkedList on the internet—and then roll up our sleeves to copy and refactor all 150 references to stack. Fun? Not at all, but we don't see any other way out.

Let's move on to the present, where our code looks like this:

Deque<Integer> deque = new ArrayDeque<>();

IntStream.range(0, 5)

.forEach(deque::addLast);

System.out.println(deque.pollLast());Over time, the code also grows to include 150 references, but now it has references to deque. We follow the same path and also put forward the theory that it'll be faster with a linked list. And now... we just change the declaration from ArrayDeque to LinkedList, which also implements Deque, and that's all it takes!

This is exactly how the Collections Framework solved the problem of missing common interfaces. It helps avoid being tied to specific implementations. For example, developers are no longer locked into something like Vector and can use the List interface instead.

At one time, finalizers (#finalize()) seemed like an excellent idea: a method that would be called when an object was destroyed, releasing system resources.

But, in practice, this idea wasn't so brilliant:

Let's start from afar. Modern Java is very flexible; even the garbage collector can be of any kind and configured in different ways. Under such conditions, it can't be guaranteed that the copy will ever be deleted.

And don't forget that the garbage collector is guaranteed not to collect an instance as long as it has at least one strong reference.

For these reasons, the logic of releasing system resources should not depend on the object's lifecycle.

If we look at the documentation for the #finalize() method, we see that it's recommended to use the AutoCloseable interface instead. It was created specifically to efficiently release resources without involving the garbage collector. The main thing is not to forget to do it.

As for tracking when an object is actually deleted, Java provides an alternative: java.lang.ref.Cleaner, which solves the problems described above.

For clarity, let's play around with Java memory and write some unsafe code using a finalizer:

class ImmortalObject {

private static Collection<ImmortalObject> triedToDelete = new ArrayList<>();

@Override

protected void finalize() throws Throwable {

triedToDelete.add(this);

}

}Here, we literally resurrect every instance of ImmortalObject that the garbage collector is about to delete, which won't please your RAM or you yourself when it crashes with an OutOfMemoryError.

This is what the equivalent code looks like with Cleaner:

static List<ImmortalObject> immortalObjects = new ArrayList<>();

....

var immortalObject = new ImmortalObject();

Cleaner.create()

.register(

immortalObject,

() -> immortalObjects.add(immortalObject)

);It's noteworthy to mention that we can also listen to the deletion of absolutely any existing object.

Stop! Have we just learnt why that approach is problematic? That's true, but it's only bad with resource management. Sometimes a Java application still needs to know that the garbage collector deletes an object. Like for what? For example, to create an optimized cache.

The class still lives up to its name, but not because we add it to a static list when we delete the instance. Instead, Runnable that acts as the listener here holds a reference to immortalObject. Now the object won't be resurrected because the garbage collector won't delete the instance. It's more idiomatic in Java and no necromancy is involved.

Finalizers were often used when working with objects that were created via JNI somewhere outside of the Java code, for example, in C++. But the mechanism was unsafe, and the finalizers were eventually replaced with a far more elegant alternative.

Few remember that Java once literally kept pace with JavaScript: JDK 8 featured the built-in Nashorn JS engine, which let developers run JS code directly from Java.

We could implement that very popular banana puzzle without leaving Java:

new NashornScriptEngineFactory()

.getScriptEngine()

.eval("('b' + 'a' + + 'a' + 'a').toLowerCase();");Indeed, it's a cool thing, but only until we realize that Java developers have to maintain the JavaScript engine.

Nashorn couldn't keep pace with the rapid evolution of JavaScript, as well as polyglot solutions appeared, like GraalVM Polyglot. These factors led to the engine becoming outdated after just four language versions (in Java 11), and after a while, it was finally thrown overboard in Java 15.

Why is GraalVM Polyglot better? While Nashorn has implemented JavaScript on top of Java, Polyglot creates an entire JVM-based platform that natively supports multiple languages, including Java and JavaScript.

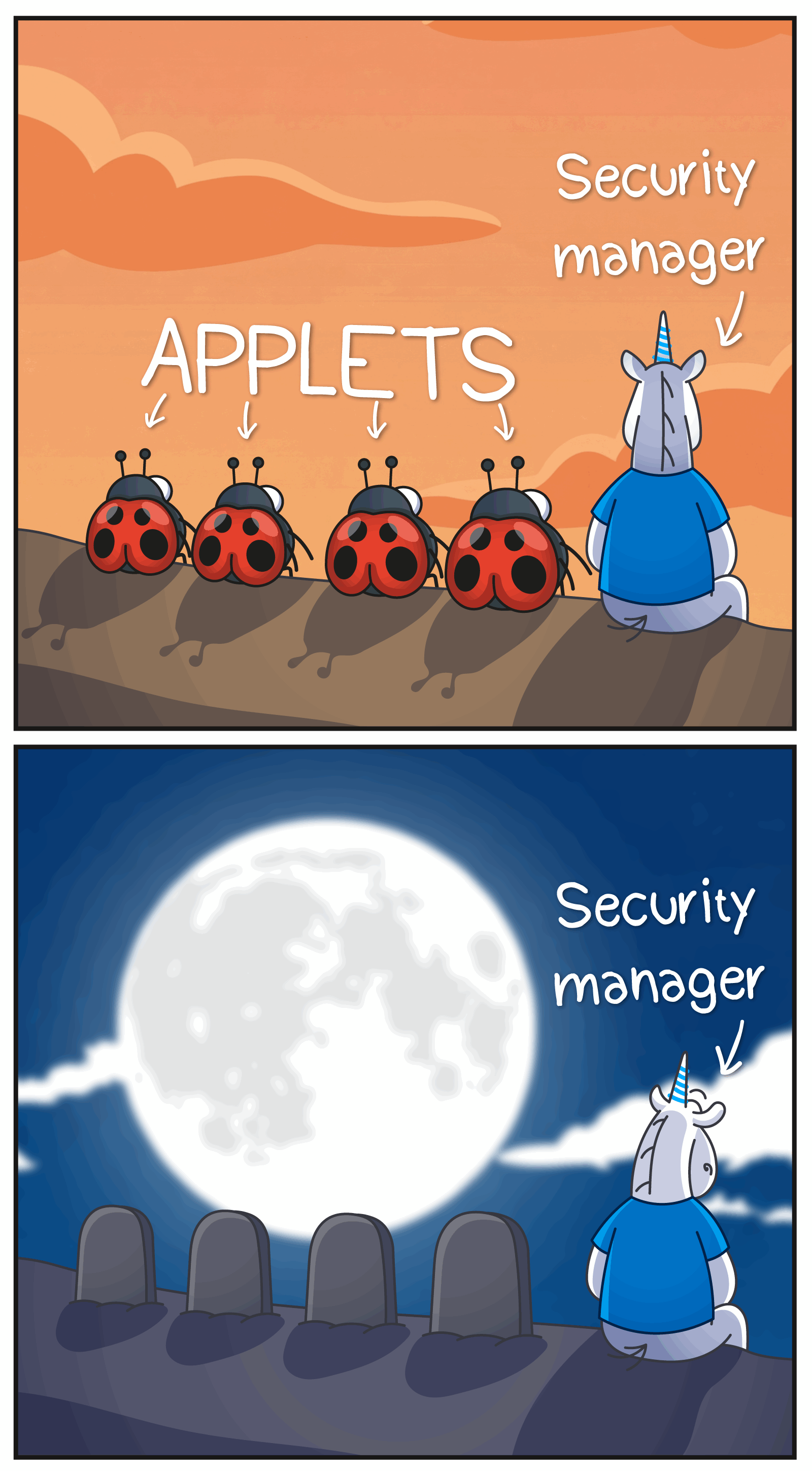

Meet another old-timer that survived until Java 17—SecurityManager.

In the days of wild applets, when Java code could be executed directly in the browser, SecurityManager was the backbone of Java application security.

An applet is a small program that runs directly in a browser and can display animations, graphics, or interactive elements, but operates under strict limitations.

But time passed, wild applets finally migrated from browsers to desktops, and then died out completely as a solution. But SecurityManager remained and was often used in enterprise applications.

But nothing lasts forever, and the Grim Reaper came for SecurityManager. Java 17 removed its entire interior and left only the facade without any logic. If we look at the entry point for installing SecurityManager, we'll only find the placeholder:

@Deprecated(since = "17", forRemoval = true)

public static void setSecurityManager(SecurityManager sm) {

throw new UnsupportedOperationException(

"Setting a Security Manager is not supported");

}How did SecurityManager work? It acted as an internal JVM guard that intercepted potentially dangerous operations and checked whether each stack element had the right to perform such an action.

What exactly did SecurityManager intercept? The list is huge, so I suggest we just look at the main points:

SecurityManager worked well in the days of browser applets, where it was necessary to keep untrusted code in a sandbox, but with the development of containerization, it became outdated.

Although SecurityManager was originally created for applets, it was used in other contexts as well. For example, Tomcat supported its use in server applications. In our PVS-Studio static analyzer, it helped solve an amusing problem: if the static class initializer in the analyzed code called System#exit, the analysis process would terminate. SecurityManager allowed us to block such operations when analyzing static fields, and something we later replaced with ASM.

By the way, even though applets as an approach were discontinued earlier than SecurityManager, they have only just begun to be removed from the JDK.

The world is changing, approaches are changing, and SecurityManager is going away.

Java removes unsafety. Literally.

Perhaps the most legendary resident of this tomb was sun.misc.Unsafe.

This class was a secret gateway into the JVM depths, where the usual language rules were no longer in force. Unsafe can easily crash a Java application with SIGSEGV.

How? For example, like that:

class Container {

Object value; // (1)

}

// ✨ some magic to get unsafe unsafely ✨

Unsafe unsafe = ....;

long Container_value =

unsafe.objectFieldOffset(Container.class.getDeclaredField("value"));

var container = new Container();

unsafe.getAndSetLong(container, Container_value, Long.MAX_VALUE); // (2)

System.out.println(container.value); // (3)In the value field (1), we set Long.MAX_VALUE (2) instead of Object and try output the value to System.out (3).

The virtual machine isn't fond of this trick, and it crashes on the last line because value contains garbage instead of a real reference to the object. And this is just one example of such an easy-to-spot error.

But why was such a dangerous mechanism added to Java?

Unsafe wasn't born as an anarchist but as a savior. Once upon a time, before VarHandle and MemorySegment (we'll talk about them later), the standard libraries had to perform low-level operations like memory management, atomic operations, or thread blocking efficiently.

But how can we do all of the above if the language prohibits you from looking under the hood? Right, we can make a gap. This is where Unsafe appeared as an internal tool for Java's own needs.

Developers intended to use it only within Java—and it even had protection against gaining external access to its instance. But what happened in Java, not stayed in Java, and developers found a way to obtain Unsafe, bypassing its protection. Behold the magic that catches an "unsafety" in an unsafe way:

var Unsafe_theUnsafe = Unsafe.class.getDeclaredField("theUnsafe");

Unsafe_theUnsafe.setAccessible(true);

Unsafe unsafe = (Unsafe) Unsafe_theUnsafe.get(null);This object allows us to torture the virtual machine as much as we want.

But don't rush to criticize the developers who dared to reach for what Java tried so hard to hide from them; it's worth remembering: the access to Unsafe helped many libraries become more efficient. For example, the popular Netty library for working with networks was forced to use Unsafe, and when a replacement came out, Netty switched to it.

So what kind of replacement are we talking about?

There are not one, but two:

These APIs aren't limited to simply replacing certain methods in Unsafe. They're powerful tools for working safely with low-level operations. For example, the Foreign Function & Memory API allows calling native functions without using the cumbersome JNI!

Java's unsafety is slowly fading into oblivion, leaving behind new, well-designed, and powerful APIs that do the same thing without fear of the conditional SIGSEGV.

Java is growing up, shedding outdated ideas, becoming safer, cleaner, and simpler. Each new API isn't just "adding another module", but closing old gaps in a more sophisticated way.

At the same time, the virtual "tomb" plays an important cultural role: it records the evolution of ideas and decisions, reminding us of the path we've traveled and forming the context necessary for the meaningful platform development.

0